Zero to One for Meditation

As someone who is predisposed to spend a lot of time in my own head, it's difficult to overstate how valuable meditation has been. And time and time again, I see friends and family tormented by pathological thought patterns, torturing themselves by repeatedly manufacturing the same negative emotions over and over. I try not to be preachy about it, but naturally I find myself often recommending meditation to those around me. Common responses include "it sounds awesome, it would be great if I could do that..." or "I tried meditating once or twice but it didn't really work..."

I'm writing this essay to help address these - my goal is to convince you that meditation will truly help your life and is worthy of your time (the why), to describe how to meditate and offer some theory that will help you get started (the how), and to curate resources to help you continue the journey.

First things first - everyone can meditate. The insight not variable.

In the West, meditation surged in popularity during the counter-culture movement of the 60s and 70s, and because of this it is often associated with some of the unhelpful and un-falsifiable woo beliefs that also emerged in pop culture at that time. But meditation itself is not a mystical and esoteric discipline. It does make any demands on your higher order perspective, opinions, or religion. Rather, it is a set of techniques that leads to consistent observations between individuals regarding the epistemology of thoughts, feelings, or any other appearances in consciousness. Meditation is a practice to understand what the nature of consciousness is actually like, to understand what your mind already is, through firsthand observation.

In the platonic ideal of science, if you read a research paper and carefully follow the experimental setup, you expect to replicate the results. Meditation is analogous; if you carefully follow the practice, you can expect to replicate the insight. And you don't have to give up your love of logic, you don't have to abandon your skepticism (in fact, it is preferable that you keep it), you don't have to believe or stop believing in a God or any higher entity whatsoever. You just follow the practice, and come to see the insight.

The Why

It's important that you have a compelling reason to want to start meditating, otherwise you will probably bounce off of the whole project. Many people find themselves drawn to meditation after a dramatic life event, like the end of a relationship, or the death of a loved one, and use it as framework for processing their personal suffering. Others might be purely interested in enhancing their own productivity and being the best version of themselves. Some people are just curious. They want to understand their own consciousness, and end up meditating as a means of research and discovery. It doesn't really matter what your reason is, just that it is deeply compelling to you, because if you don't have a why, you will probably find it difficult to force yourself to meditate.

If you already have a why, that's great! If not, the rest of this section shares a bit on how meditation has impacted my life personally - maybe it will help you find a reason.

Adopting a meditation practice and integrating the accompanying insights into my life has likely been the single most impactful boon to my personal growth and general well-being. It's a way to reveal and understand the deep truths of my being, to illuminate the parts of the psyche that hide in dark corners. It is also the single most informative technique I've discovered for understanding what my conscious experience actually is. On the productivity side, it's like unlocking a cheat code, or being granted a superpower. If I'm feeling stress, sadness, or any other negative emotion, I can meditate, see it for what it is, and watch it fade into nothingness. If I am feeling distracted and spaced out, I can meditate and watch my focus return. Or, if I'm feeling a little too high on life, I can meditate to maintain a healthy dopamine baseline and avoid the motivation crash that usually follows a few days after those moments of achievement and euphoria.

Alternatively, I can do none of this. It's a choice. For me, the point isn't to cease all desire and suffering and permanently exist in a blissed out state of oneness with the universe; I've caught glimpses of what that is like, and it seems to come at the expense of agency and impact of the world. I think negative emotions exist for a reason - they signal a change in environment (either internal or external) is needed. Positive emotions exist for a reason - they signal reward or satiation. I don't want to suggest that maximization of positive or minimization of negative emotion is a path to a meaningful life, but I do think it's reasonable to place some amount of intrinsic value on them as guideposts for my experience. So I'm not looking to reach Nirvana; I don't want to exist in pure equanimity. Rather, the value of meditation in my life comes from recognizing what the nature of consciousness is actually like, and providing a framework, or toolkit, for adjusting the state of consciousness to better meet my goals. I use it as a destination for my attention. A home base to return to in between focused tasks. Our neurophysiological systems are in many ways inadequate for the emergent complexity of modern civilization, especially the demands on attention. Rather than having my actions subject to the whims and variable willpower that spontaneously manifests from one moment to the next, I meditate to adjust the state of consciousness itself in order to elicit a set of actions that leads to the life I want. Critically, at no point in this does meditation offer anything in service of a judgement toward a certain set of goals or prescription of what constitutes a meaningful existence. That's up to you to figure out.

How

First, it's important to note that there are two aspects of the whole program - the theory, and the practice. The practice is more important, but if you read the theory too, you can get better results from the practice. Think of it like playing piano. If you're self-taught but practice obsessively, you'll probably be a decent pianist, but it might take you a while to rediscover essential music theory concepts that would take your playing to the next level. Alternatively, if you spend all your time studying theory, you can probably impress other people with your knowledge and feign the appearance of an expert, but you can't actually play the piano. The most efficient allocation is to spend time learning new theory every so often (say, once or twice a week), then dedicate most of your efforts to practicing (every day). Meditation is exactly the same. You want to balance intermittent theory with regular practice.

I'm enamored by the world of ideas. I like theories, whether they be physical or metaphysical, so for me it was effective to dip my toes into the theory first, in order to further solidify motivation to practice. I'll follow that pattern here.

Theory

There are multiple types of meditation techniques. The three that I play with are Zen, Vipassana, and the Jhanas. Vipassana is the most common in the West, and maps to what we typically refer to as mindfulness, so we'll focus on that approach.

What is Vipassana Meditation?

Vipassana, which means to see things as they really are, is one of India's most ancient techniques of meditation. It was rediscovered by Gotama Buddha more than 2500 years ago and was taught by him as a universal remedy for universal ills, i.e., an Art Of Living. This non-sectarian technique aims for the total eradication of mental impurities and the resultant highest happiness of full liberation.

Vipassana is a way of self-transformation through self-observation. It focuses on the deep interconnection between mind and body, which can be experienced directly by disciplined attention to the physical sensations that form the life of the body, and that continuously interconnect and condition the life of the mind. It is this observation-based, self-exploratory journey to the common root of mind and body that dissolves mental impurity, resulting in a balanced mind full of love and compassion.

The scientific laws that operate one's thoughts, feelings, judgements and sensations become clear. Through direct experience, the nature of how one grows or regresses, how one produces suffering or frees oneself from suffering is understood. Life becomes characterized by increased awareness, non-delusion, self-control and peace.

- https://www.dhamma.org/en/about/vipassana

The most important phrase here is "disciplined attention to physical sensations." That's the gist of it. You start by exerting disciplined attention to your bodily sensations to develop awareness of your field of consciousness. Every movement of the breath, every sound, every itch takes place in the same field of consciousness. It's kind of like playing battleship - if you focus on detailed observations, you can start to build up a sense of what the full picture is like. Experiencing this firsthand and recognizing the nature of consciousness as it relates to physical sensations is step one. From there, you can start to shift your attention to observing thoughts and feelings in addition to physical sensation. Your mind is interconnected with the body, so every thought, every feeling, every idea also takes place in that same field of consciousness. When you see that for what it is, you can start to recognize the emptiness of all thoughts, feelings, sensations, perceptions, memories. You can recognize the emptiness of consciousness itself, and in doing so, build up the muscle to control your attention.

Practice

The exercise is as follows - sit down, either cross legged or in a chair, keeping your spine straight and the crown of your head pulled toward the sky. Close your eyes, and pay attention to your breath. When you notice you are distracted or lost in thought, just return to the breath. Try to do this for at least 20 minutes. That's all.

Why is the breath? There really is no reason. There's nothing magical about it, but it's always there. You could just as easily focus on sounds, or your heartbeat, or something in your visual field, but this would require more setup. The breath is trivial and convenient, making it an ideal object to rest your attention on. So focus on the breath, wherever you feel it most clearly. For me it's in the chest, around the body of my sternum, but many prefer to focus on the airflow at tip of the nostrils. It doesn't really matter. Again, the point is just to have a place to direct your attention. Try to cover the breath with your awareness, paying attention to it for the entire cycle of inhalation and exhalation, leaving no spots uncovered.

You'll quickly notice that it's not working. Unless you have some prior experience, you will be physically incapable of emptying your awareness of everything except for the breath. You'll find some thought appear, or maybe sense the contact of your legs on the floor, or feel an itch on your face. That's ok - just return to the breath. After a couple more seconds, maybe you'll remember a conversation you had yesterday, or think about the errand you have to take care of when you're done meditating. And then you remember you're supposed to be meditating, so you return your attention to the breath. Moments later, you're back to noticing. You find that no matter how hard you try, you cannot stop these thoughts and sensations from appearing, even if they only pop into existence for a split second. And further, that this is the state you always live in. This is what your existence is actually like - your attention is constantly jumping from one object in consciousness to the next, with no volitional control.

This is the practice. It is this act of directing your attention, and noticing what happens. The goal isn't to permanently rest your attention on something trivial like the breath, although you'll find that you get better and better at doing this over time. The goal is the insight that comes from the practice, the experience of recognizing what your conscious experience is like on a more granular level than you normally are able to. Meditating is simply conducting this exercise of directing your attention, noticing distractions, and redirecting your attention back.

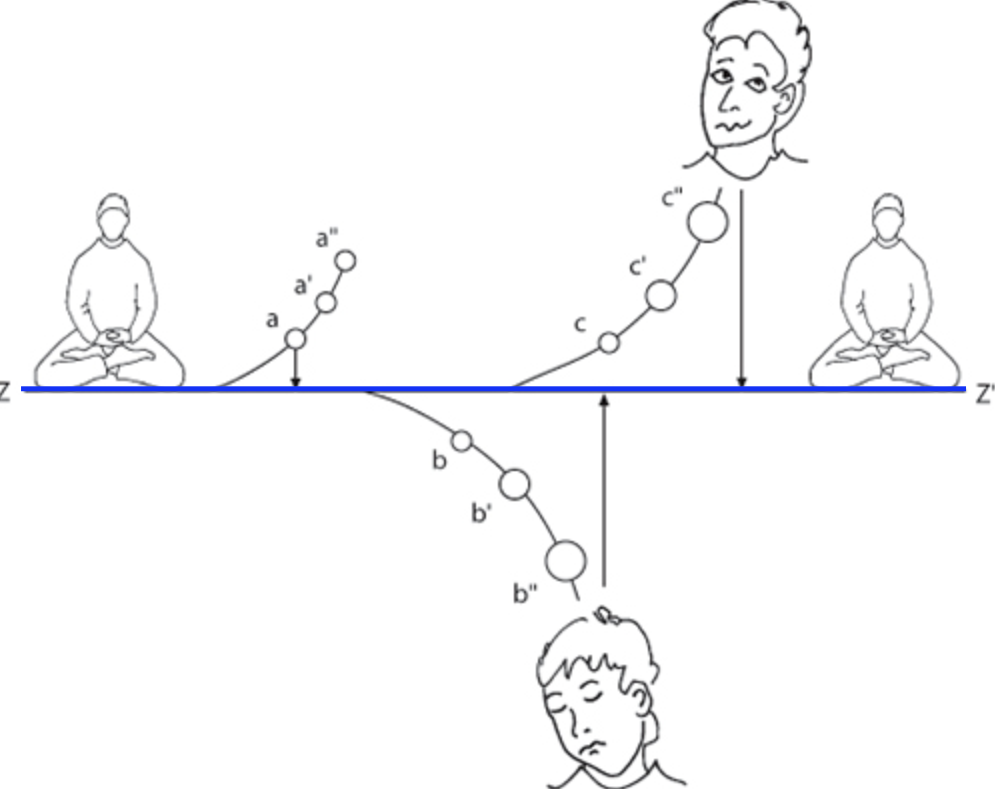

This diagram (taken from Opening the Hand of Thought - ) helped me a lot when I was learning to meditate. Meditation is not about staying on the blue ZZ' line for as long as possible. The point is that you're returning to ZZ' every time you get distracted, and doing this as quickly as possible. This entire process of paying attention, getting distracted, noticing distraction, and returning your attention is meditation. As you continue to meditate, you'll find that you are spending more time on ZZ', which means your resolution for noticing is higher. Maybe instead of only noticing you're lost in thought at c'', you instead are able to notice at c', and then c. This increased granularity of noticing lets you uncover a deeper understanding of your experience, regardless of what it is that you're experiencing.

Paradoxically, I think the simplicity of meditation can be a blocker for a lot of people. Given the instructions of the practice, it's hard to believe it can have a substantial impact on your life. The advantage meditation has is that you don't have to take anyone's word for it - if you dedicate time to the practice, you can see for yourself. If you try meditating and aren't finding anything interesting, it might be a sign that you could benefit from more of the theory, or that your attention is pulled in so many directions that you haven't yet managed to quiet the mind. You might be following a train of thought, ending up at c'''''', and mistaking that line for ZZ'.

Treat it like a playground - you are exploring the nature of your own mind, of your own being. Surely you can find some interesting discoveries in there. Just notice whatever that is, then return back to the breath.

Recommendations for Future Reading

There are thousands of years of accumulated wisdom on meditative practices. Many very smart people have dedicated their entire lives to pursuing meditation and the accompanying insight. Contrasting that, there are dozens of mediocre self-help mindfulness books released every year. It can be difficult to know where to start, and parse what is worth your time, so below I've collected a few of the books on the topic that have deeply resonated for me. I've arranged them in roughly the order I'd recommend reading them, included a brief description, and highlighted ones I've found to be truly special. Note - while I've described the basics of Vipassana above, this reading list transitions into Zen practice and theory.

- Wherever You Go, There You Are - Jon Kabat Zinn

- Easily digestible and highly practical meditation guide from a medical physician, implicitly targeted at those seeking actionable practices for stress reduction while avoiding (most of) the woo.

- Siddhartha - Herman Hesse

- A classic work of literary fiction that merges ideas from Nietzsche and Jung with Eastern philosophy. An comfy starting point for dipping your toes into the theory.

- Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind - Shunryu Suzuki

- Loose introduction to Zen, repeatedly espoused by Steve Jobs. It's a classic. Simple, easy to read, and full of wisdom broadly applicable to both meditation and daily life. I get a similar aura from it as Marcus Aurelius - Mediations, but for Zen instead of Stoicism.

- The Creative Act - Rick Rubin

- A case study for how mindfulness can be applied to real life. Rubin implicitly shares how meditative insights fueled his legendary career in music production, and explicitly generalizes these lessons to the broader creative process using his characteristic sage-like and prosaic style.

- Opening the Hand of Thought - Rosho Uchiyama

- Phenomenal introduction to Zen - clear, direct, and modern, with a nice blend of theory and practice. Perfect for building towards a daily mediation practice.

- The Heart Sutra (Red Pine Translation)

- One of the essential texts of Zen (and Mahayana, more broadly). Part of the Prajnaparamita or 'Perfection of Wisdom'. The Red Pine translation offers an excellent line by line breakdown of the sutra. If you have a regular meditation practice and are curious about the whole enlightenment/nirvana/emptiness thing, this is a phenomenal book for beginning to deepen your insight.

- The Diamond Sutra (Red Pine Translation)

- Another part of the Prajnaparamita, complementary to the Heart Sutra, but with more of a focus on non-duality, the illusion of the Self, and attachment. Again, the Red Pine translation is highly recommended.

- The Seeing that Frees - Rob Burbea

- Dense, demanding, and revelatory. If your goal is to truly deepen your understanding of emptiness/enlightenment and level up an existing meditation practice, this is the probably the best book to read.